People using the skills audit method should have a certain set of competences to effectively support the client. A career counsellor should motivate their client and present the benefits of doing the skills audit in an appropriate way. This is often a long process that requires considerable commitment on the part of the client. Another important skill is building a relationship with the client going through assessment, based on trust and providing a safe space for talking about various aspects of life. The audit concerns not only professional and educational matters, it often affects personal life, which may be associated with difficult emotions.

The diagnostic part of the Skills Audit Method is based on semi-structured interviews. It is therefore very important that the counsellors conducting such an interview know the guidelines for doing this and have experience in conducting biographical and behavioural interviews.

In addition, the counsellors should—depending on the client’s needs and capabilities—use additional diagnostic tools (e.g., tests to examine aptitudes, interests and skills; tools to assess motivation) and, where necessary, be qualified to use them.

When conducting a skills audit, it is important to know the labour market (or its specific sectors), education and training opportunities, and the sources of knowledge about them. In addition, the counsellors should have knowledge about the concept of lifelong learning, qualifications, the Integrated Qualifications System, and validation. This information is used to establish the client’s development plan.

The ability to analyse and synthesise information is also crucial, so that at the end of the skills audit, the counsellor can effectively summarise and discuss the results of the process with the client, taking into account their goals and needs. The ability to create plans to help the client further develop their competences is also important.

The Regional Labour Office in Kraków has prepared a market qualification “Conducting the Skills Audit Process”. The learning outcomes listed there may be very useful for people who want to introduce the skills audit into their counselling work.

Undergoing a skills audit is voluntary. This means that the process will not start without the consent of the client, who can opt out at any time.

The client makes all decisions regarding the direction and scope of activities during the skills audit. This also applies to the developed materials and decisions about what to do with them later.

The conversation with the career counsellor should take place in a private setting. Anything the person undergoing the audit shares with the counsellor stays between them. Only the client can decide whether or not to make the skills audit results available to third parties (e.g., a potential employer).

The Skills Audit Method is based largely on the client’s own work (self-reflection, portfolio preparation). The counsellor’s role is supportive and guiding during this process. They ask questions that help the client become aware of their own competences, knowledge and skills; select additional tools that help the client see a broader picture of themselves; support the client in their work between meetings (e.g., by providing assignments or forms to complete at home). Above all, the counsellor helps in using the right words to describe skills, knowledge and social competences and to organise them based on what the client wants to achieve.

The following concepts have been defined for the purposes of working with the method. This means that they may have slightly different meanings in other contexts.

By “competences”, we mean:

Competence identification is a process aiming to:

More on this topic can be found below.

This is the process of collecting evidence (e.g., work performed by a person, the opinions of superiors) and descriptions of situations that prove the possession of specific competences.

More on this topic can be found below.

The text contains icons indicating elements that you should pay attention to.

ATTENTION

TOOLS

MEETINGS

GOAL

COMPETENCES

PORTFOLIO

FURTHER DEVELOPMENT PLAN

The Skills Audit Method (SAM) is used to recognise, describe, and document the competences a person has and to prepare development plans for further educational and career paths.

It can be applied in various contexts. These include:

The Skills Audit Method should be conducted while observing the guidelines presented earlier.

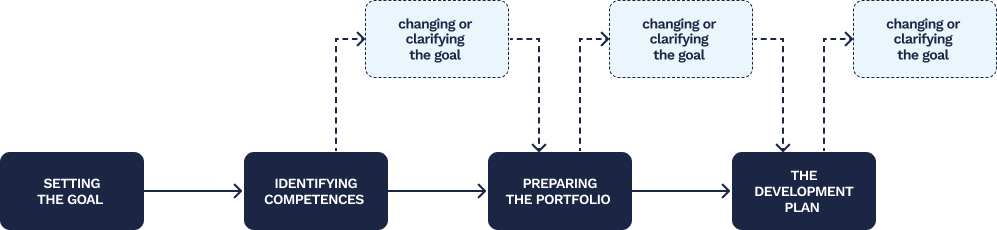

Figure 1. Steps of the Skills Audit Method

It is important to remember that the skills audit serves the client first and foremost, so that it can be adapted to their needs.

These steps do not have to be done in separate meetings. Some of the steps may occur simultaneously. For example, knowledge, skills and social competences can be identified with the client on an ongoing basis and the portfolio can start to be assembled before the diagnosis stage ends.

Depending on the client’s goals and needs, only some elements of the skills audit may have to be implemented.

The duration of the audit will vary depending on the individual. This pertains to both meetings (direct or online) and the length of time a client needs to accomplish their independent work.

Working with someone who wants to define their career or educational goals through an audit may require 4–6 meetings (a minimum of 2). In turn, you will most likely have to meet 3–4 times with a client who has clarified the purpose of the skills audit. A client seeking a specific job or qualification will usually want to shorten the counselling process. It may happen that you will only meet 1–2 times.

The recommended length of a meeting is approximately 1.5 hours. However, the length can be adjusted to the client’s needs, taking into account organisational possibilities.

Additional guidelines for conducting the audit:

The first step in the skills audit is to introduce the client to this process – explaining what the audit is, what it consists of, and the benefits it can bring, as well as presenting the work involved in using the Skills Audit Method.

The basic issue at this stage is to determine the client’s educational or professional goal. What do they want to achieve with the skills audit? How much do they already know about themselves and how much do they hope to learn as a result of the audit?

Zbigniew will be retiring in a few years. He doesn’t know how he will cope financially then, so he would like to continue working.

He has spent almost 30 years in a company manufacturing public transport vehicles and believes that he knows a lot in this field. However, he is not convinced that these skills would be useful in another job.

He also knows that finding a job at his age is difficult. Moreover, he has no experience in looking for a job and is unfamiliar with the market.

Zbigniew needs help in determining exactly which competences he has, and where they could be used.

Maria is studying international relations. To earn some extra money, she works at the reception desk of a fitness club on weekends. She has many interests but nothing that she is passionate about. She wants a stable job with a nice atmosphere, but doesn’t know which industry or job position might suit her.

She doesn’t think she has many skills, even though she has always performed well academically. She feels quite lost—she’s never really given much thought about herself and her goals.

Maria needs help in getting to know herself, understanding her skills, and sorting out her values.

Elena came from Ukraine to study management (the secondary school completion exam is taken there earlier than in Poland). Her scholarship does not cover all of her living expenses, so she wants to find a job – ideally one that relates to managing a team, but she would also be happy with a part-time job. Previously, she helped her parents run a guesthouse, worked, among others, at the reception desk, handled social media, and managed the work of others. In Poland, as a minor and without citizenship, she has very limited opportunities to find a job. She does not speak Polish fluently, which is an additional barrier. Elena needs help with discovering what she needs to do to find employment as quickly as possible.

If the client’s goal is to become employed in a specific industry, you probably don’t need to conduct a broad survey of all the competences they have. Knowing the goal they want to achieve, you can more easily choose questions for the interview and – if needed – additional tools. The area in which potential competence gaps are revealed may also depend on the client’s goal. A person who is not very good at using computers and wants to work in a shoe store will probably want to know whether they need to develop communication skills.

When starting the audit, a person may not yet have any specific career or educational goals in mind (as Maria’s example shows). However, this does not mean that they have no expectations. You should discuss them and decide together on the next steps during the skills audit.

A person who needs help in preparing a portfolio for a specific recruitment or market qualification will not necessarily want to prepare a development plan (deadlines for submitting documents are usually short, and when applying for a specific job, the client will know know what to do and when).

A person who started the audit because they need a diagnosis that is as broad as possible may decide to collect evidence for each identified competence. However, someone who wants to retrain may consider this unnecessary and focus on preparing evidence of key competences in a given area.

Feedback is a summary of the entire process prepared by the counsellor for the client undergoing the audit and should refer to the results of its individual stages. The more extensive the scope of the skills audit, the more should be included in such a summary (which will also take more time to prepare). Depending on the client’s needs, it may be enough to summarise the entire process and discuss the portfolio and development plan, or it may be better to prepare written feedback summarising the client’s work on the skills audit.

The development plan is intended to help the client achieve their goal. Such a plan will usually set out the steps that need to be taken to achieve the goal.

Sometimes the client’s goal will predetermine the steps to be taken. This is the case for Maria, who intends to apply for a specific job position. The outcome of the skills audit may help make this plan more specific (e.g., with steps to address minor competence gaps), but will not change it.

Each of the above activities takes time. An extensive diagnosis of competences, which will consist of a biographical interview, a behavioural interview and additional tools (e.g., the Competences Assessment Tool [Narzędzie Badania Kompetencji] developed by the Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Policy calls for more meetings than determining whether the client meets the requirements contained in a job advertisement. Gathering evidence of possessing competences may take more time if the client has decided to prepare an extensive portfolio. Often during (or as a result of) the skills audit, the client’s goal changes. They may clarify it, add to it, or abandon it altogether. This is natural and counsellors should be open to this possibility. This means, however, that the initial arrangements may have to be changed during the skills audit process.

The first meeting is intended to collect basic information about the client. During this time you can:

Zbigniew decided to proceed with the skills audit after an initial conversation with the counsellor. He briefly presented his situation and learned basic information about the Skills Audit Method.

The counsellor explained to him, among other things, the benefits he may derive from doing the skills audit. Together they agreed on how they will continue their work, as well as the date and scope of the first meeting of the skills audit process.

At this stage, you help the client see what they already know and are able to do based on their work and non-work experiences, as well as their learning.

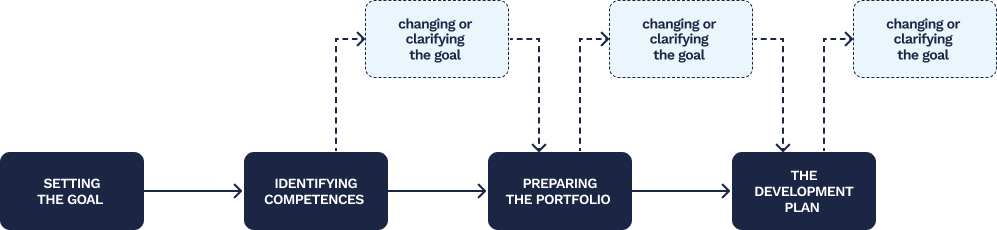

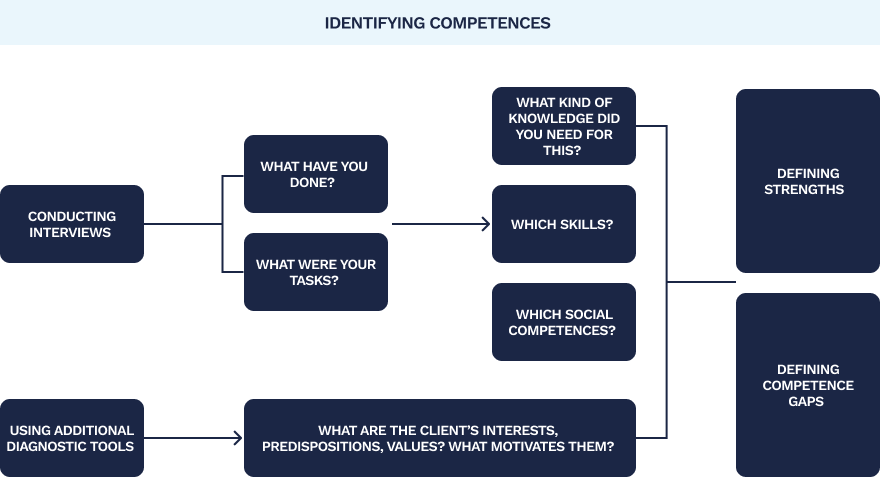

Figure 2. Competency identification stage

The client may be doing the audit for various reasons, and these will significantly impact the scope of identified competences or the tools used.

They may want to use the audit to define or clarify their educational and career goals. This means that they will need as broad as possible diagnosis of competences, aptitudes, interests, and values.

The counsellor conducted biographical and behavioural interviews with Maria. She also completed the “Schein’s Career Anchors” test. In order to better recognise her aptitudes, the counsellor also offered her the “Key to a Career” test. She had the most difficulty in isolating specific competences in various activities (“Working at the reception desk requires having good contact with people; it’s probably a soft skill, right?”). It took two meetings, but the self-reflection and discussion with the counsellor allowed Maria to recognise her values, aptitudes, and talents. This allowed her to narrow down the field of activity in which she would like to work. During this stage, the counsellor recommended that Maria learn more about the realities of the job market (on the basis of sources provided by the counsellor). She learned more about the type of positions she could apply for while still studying.

The client may be doing the audit for various reasons, and these will significantly impact the scope of identified competences or the tools used.

They may want use the audit to define or clarify their educational and career goals. This means that they will need as broad as possible diagnosis of competences, aptitudes, interests, and values.

Elena’s skills audit began with a biographical interview. She talked about her education, plans, and hopes for her stay in Poland and about the work at her parents’ guesthouse. The counsellor focused mainly on this last aspect and moved on to the behavioural interview. Elena was questioned mainly about her responsibilities at the guest house, where she was in charge of social media, staffed the reception desk for a few hours per week and, when needed, substituted for her father to supervise the cleaning staff. After writing down her tasks, Elena and the counsellor began to think about which skills each of them required. It took them another meeting, but as a result, Elena realised that running the social media of her parents’ guesthouse required knowledge and skills that are valuable in the job market – she would be able to use them in other areas. Between meetings, Elena took the “Schein’s Career Anchors” test and searched for information about the Poland’s job market (based on sources indicated by the counsellor). At the end of this stage of the audit, they identified areas for further work and training needs. Elena learned that she would find a job more easily if she develops her teamwork and self-presentation skills. She should also learn more about organisational culture (for example, she didn’t know much about dress codes until now).

The client may also want to determine to what extent they meet specific requirements (e.g., the competences listed in a job description or the learning outcomes of a specific qualification). In this case, making a list of competences will be the starting point of the audit. The counsellor’s role will be to help the client determine whether their knowledge, skills, and social competences align with the list of requirements.

However, this does not mean that other competences identified during the audit should be overlooked – especially if they can be used in various contexts (e.g., digital skills, communication abilities, teamwork).

In order to identify the knowledge, skills, and social competences a client has, we propose the use of the biographical and behavioural interviews.

Zbigniew thought he could only assemble buses. When asked about his skills, he mentioned first those that he needed in his work as a mechanic. He had heard about “soft skills”, but did not attach much importance to them. In his opinion, a specialist should first of all know his job (“be able to diagnose and repair a faulty machine, know how to assemble a vehicle”). He called professional experience whatever goes beyond the hard skills. The counsellor started by discussing with Zbigniew his experiences in various areas of life. As part of the biographical interview, Zbigniew was asked, among other things, about his professional experience, education, courses, training and qualifications, interests, social activities, and knowledge of foreign languages. This took almost two meetings. As a result, several areas were identified to focus on during the behavioural interview. This consisted of talking about Zbigniew’s individual activities and the competences each of them required. Additionally, the counsellor asked Zbigniew to fill out the Competences Assessment Tool. As a result, it turned out that Zbigniew had many skills unrelated to mechanics (including culinary, mathematics, and managing a small team).

During the interviews, the counsellor and client identify what has been done so far – both in the context of work, education, and hobbies. The reference point can be a list of requirements (e.g., a job advertisement, a specific qualification). With the counsellor’s help, the client recalls specific situations and names the knowledge, skills, and social competence they can demonstrate (or have learned) from them. Depending on the client, the counsellor decides how long each interview lasts. Usually one interview smoothly transitions to the next, with no clear boundary.

The starting point of the interview may be the educational and professional history prepared earlier by the client, i.e., a list of the schools attended or jobs they held, but also other activities they did as part of a hobby or their family responsibilities.

It may turn out that the client’s resume or educational and professional history contains enough information to achieve their goal. In this case, the biographical interview can be shortened or completely omitted.

Many methods and diagnostic tools (e.g., vocational aptitude tests) can be used in the audit. Their choice depends on the needs of the client and the stage of the audit being conducted (e.g., diagnosis, development plan).

In some cases, the client can do a self-assessment of their competences (in the context of a specific list of requirements). However, it is important to show them the right tools to use and instruct them on how this should be done. It is always worth discussing the results of such a self-assessment together.

Depending on the client’s needs, the skills audit may be finished at this stage.

At the end of the diagnosis, the client’s strengths will be visible (their competences, aptitudes). This part of the audit also enables the client to see what they still need to improve. The goal specified at the beginning of the audit process can serve as the starting point for determining competence gaps.

As a result of the identification stage, the client can define, clarify or change their educational and professional goals.

As seen in Maria’s example, there are many diagnostic methods and tools that can be used in the skills audit in addition to the biographical and behavioural interviews (e.g., professional aptitude tests). They are chosen depending on the client’s needs.

Examples of additional diagnostic tools

The next step is to save the results of the diagnosis. Linking the client’s experiences with competences based on the biographical and behavioural interviews makes it easier to define the client’s knowledge, skills, and social competences. Depending on the client’s goals, it is also worth saving other elements identified during the diagnosis, e.g., aptitudes, values, talents.

How to describe competences

In writing down the identified competences, you will mainly describe them by using existing standards:

Sometimes, however, it will be necessary to describe the knowledge, skills, and social competences a client presents because they are not found in any of the standards. In this situation, it is worth remembering to:

Using operational verbs is recommended to describe competences. These are verbs that name actions which can be observed, checked, and assessed. In other words, they are used to describe activities that are intended to be measurable. More about operational verbs can be found in the Catalogue of Validation Methods prepared by the Educational Research Institute – National Research Institute.

Elena managed the social media of her parents’ guesthouse. When trying to identify specific competences, she first divided the sheet into columns: knowledge, skills, social competence. She put a question mark on the last one, because she wasn’t sure if using Facebook actually required them. Then she wrote down the competences she needed to do this task in very general terms (“knowledge of Facebook, Instagram, Twitter”, “computer skills”). With the help of the counsellor, she started to break down the individual entries into smaller parts and specify them further. As a result, the following competences were included in the columns:

It is worth remembering that the list of competences is the basis for reflection on what the client needs most in a given context – the most important elements can be selected from the list for a given job, qualification, etc. The broader the list, the more versatile it will be in the future. It should be noted that a broader list requires more work. Some clients will prefer to focus on one area rather than doing a full audit and writing down all the competences they have acquired throughout their lives.

An integral part of the Skills Audit Method is preparing a portfolio, that is, a list of the client’s identified competences with evidence of their possession.

Figure 3. Stage of preparing the portfolio

The size of the portfolio – the number of competences the counsellor and client decide to include and link to evidence – depends on the goal defined during the skills audit.

Preparing the portfolio

A counsellor recognizes certain competences a person has, but cannot certify them on the basis of: “Mr. X knows Y and can do Z.” Moreover, if the client does not believe that they have certain competences and aptitudes, they will never consciously use them or may never develop them. Preparing a portfolio can help with this.

This process requires certain mental effort. The client should reflect on each competence; select or describe evidence proving its possession; sometimes choose one or two best examples from several. This is often a tedious and time-consuming process. However, as a result, the client is more aware of what they know and are able to do. At the same time, at the end of the audit, they have tangible proof of their competences in the form of evidence collected in the portfolio.

One of the key benefits of preparing a portfolio is to strengthen the client’s confidence that they have specific competences and will be able to confirm them if necessary. Collecting evidence has a particularly strong impact on increasing self-esteem. This may be important especially for clients in a difficult professional situation (e.g., after losing a job, being unemployed for a long time, etc.), but also for those who do not have a very extensive professional career.

Collecting evidence with the assistance of a counsellor can help the client see the importance of confirming competences relating to interests or hobbies (e.g., artistic drawings made by architects), which seem to be unimportant or are not valued as much as professional work. External confirmation that such evidence has value is important here. Without it, this type o evidence is often downplayed by the client.

This is particularly important in the context of recruitment processes. If the client has prepared a portfolio, they gain confidence in being able to confirm and explain each of the points included in their CV.

This is particularly beneficial for clients who, for example, are applying for jobs in state institutions, positions announced in the Public Information Bulletin (BIP) or by entities participating in public tenders. When saving documents to an electronic portfolio, an additional benefit is having a collection of scans stored in the cloud. They can be accessed anywhere.

When working on a portfolio, the client usually does in-depth work and thinks hard about what they actually know and can do. This enables them to describe the skills that really make them stand out in a CV, instead of using generic statements such as “ability to work with people” or “good communication skills”.

A client’s review of the evidence they have, especially formal documents, can help them set career goals (“which skills have been demonstrated in this way”; “how significant is the evidence gathered”; “which direction can be taken?”). This can be a starting point for exploring changes in their career path.

Collecting various types of evidence avoids wasting time on formally confirming competences for which the client has many other types of evidence (a skilful collection of informal evidence can replace, for example, postgraduate studies). If the client is thinking about attaining a market qualification, evidence allows them to assess their own skill level. This enables them to decide how to improve their skills (e.g., whether training is needed or rather a shorter internship).

Preparing a portfolio teaches a person to collect references, videos, photos of achievements, work samples, articles published on the Internet, projects, and written evidence of participation in training workshops, conferences, and volunteer projects. This prevents situations where, after many years, it may be difficult or impossible to obtain the evidence.

Almost any product created by a person can serve as evidence of competence, but so can the opinions of others or a description of a situation.

Zbigniew has prepared an extensive portfolio, including evidence of as many identified competences as possible. With the help of his counsellor, he included not only certificates of completion of vocational school and various courses. He also added a detailed description of how he trained younger colleagues to use a new tool and added the opinion of his direct superior on this subject. He also used part of a video promoting his company at a job fair, in which he demonstrated safety tests of assembled buses (thus demonstrating his knowledge on the subject as well as his presentation and communication skills).

It is worth encouraging clients to create a physical portfolio (folders for paper diplomas, certificates or a folder on a computer or in the cloud for scans and other files) – this way they will be organised in one place. However, from the point of view of the counselling process, just thinking about what evidence can prove one’s competences and creating a list of them with a description serves the same function as the physical documents collected – it teaches the client to think in terms of confirming competences. It can also serve as a practical aid in recruitment processes (e.g., recalling key evidence before a job interview).

It is important that the evidence refer to specific knowledge, skills, and social competences and that it can be shown to a third party.

Examples of evidence confirming competences include:

How to develop a portfolio?

The starting point for preparing a portfolio is to ask: “How can I best demonstrate to someone else that I actually have knowledge of a particular topic, have a certain skill, or possess social competences?” Depending on the answer, either actual evidence or descriptions of evidence are attached to the portfolio. It is also helpful to include a comment about the situation in which the competence was demonstrated.

It should be remembered that one piece of evidence (or description of evidence) can show that a person has more than one competence, as well as that one competence can be confirmed by more than one piece of evidence (or description of evidence). However, it is important to clearly indicate which evidence confirms a given competence. Clients may disregard certain evidence – especially evidence not relating to work (e.g., associated with hobbies or volunteering). Therefore, it is worth discussing this with the client on an ongoing basis.

It is the client who decides which competences they want to support with evidence. These may include all the competences identified in the diagnosis stage, key skills in a given area, or competences selected for a specific job application.

But nothing prevents the preparation of as broad a portfolio as possible, which will be treated as an “evidence database”. Depending on the needs, the client will then be able to select the evidence required for subsequent job applications (when changing jobs, all that would be needed is to select a new set of competences and the history and documents assigned to them).

Preparing a portfolio can potentially be the most time-consuming stage of the process. For this reason, it is recommended that the topic be introduced to the client early on and to encourage them to begin documenting their competences from the very beginning. Even if not all competences have been identified yet, this approach prompts the client to start thinking about possible evidence, which can also help guide and focus their thinking.

As the counsellor, you are a consultant in this process:

If the client’s goal is to apply for a job in which presenting a portfolio is a requirement, you should focus on:

The portfolio can be in paper or electronic format. If you and your client decide on a digital version, it is worth using the My Portfolio tool.

It allows the client – alone or with the help of a counsellor – to identify and write down competences, point to the evidence confirming them, and prepare a plan for further development.

By using My Portfolio, the identified competences, selected and documented evidence are all saved by the client in one place, in the form of files and links. This can also be limited to just creating a list and keeping the actual evidence in another place, e.g., on the client’s computer.

When preparing a portfolio, you can use a simple form, available in DOC format, which can be freely edited to suit the client’s needs. If necessary, the form can be printed.

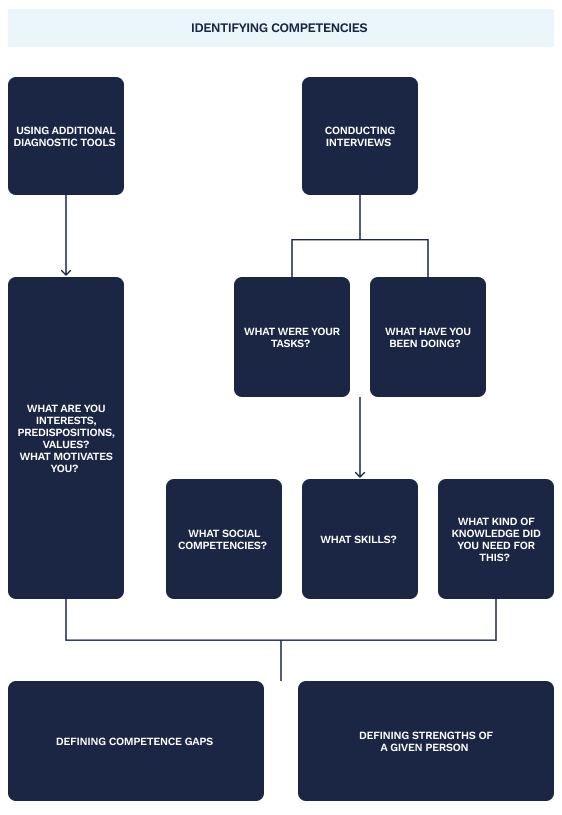

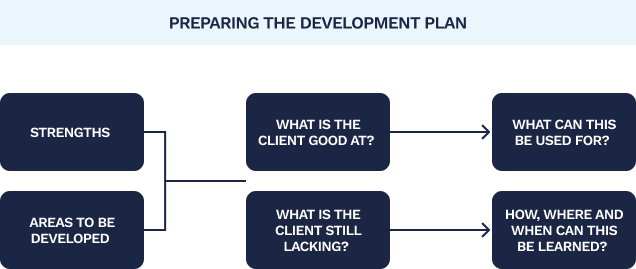

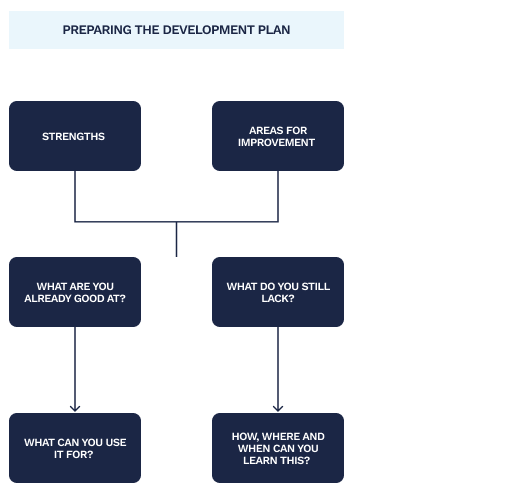

The last step in the skills audit is preparing a development plan.

Figure 4. The stages of preparing a development plan

The development plan is primarily used to determine – step by step – what needs to be done to implement the client’s goal(s).

The development plan

With a development plan, the client can make optimal use of the results of the counselling process. Identifying strengths and competence gaps is only the first step. Preparing a plan helps to direct the client’s thinking about how they can use their competences, as well as towards what needs to be done, in which order and when. Even if it is not possible to implement the plan, the very act of determining a path of further action makes the goals more realistic and limits “wishful thinking” about a career.

At the same time, preparing a development plan can strengthen the client – it gives them a sense of agency and a goal (or goals) to achieve within a set period of time.

An additional advantage of the development plan in the skills audit is that it can serve an educational function. By preparing the plan, the client learns to define goals and plan further actions.

A development plan may be created at various stages of the skills audit. This will mainly depend on the client‘s goal.

When preparing the plan, you can start from the list of competences made earlier. Determining what the client knows and is able to do, and what they cannot, helps in deciding the direction that may be taken. This is especially needed in the case of people who identify their future goals only after doing the skills audit (for example, Zbigniew or Maria).

However, it sometimes happens that the plan is developed at the beginning of the skills audit. This occurs when the client has such a specific goal that it is a plan in itself. Making a plan at the beginning of the skills audit helps the client focus on the resources that are important for refining or revising the goal. Such a plan can, of course, be modified and updated in relation to resources.

A client with a specific goal (e.g., preparing for a particular job) may have doubts whether preparing a development plan is worth it.

Plans can still be useful here – they focus on mapping out a future in a chosen industry or developing a specialisation in a profession. In addition to planning personal development, thinking about the future can have a very practical dimension. Having plans beyond “the next job interview” can help a person perform well during recruitment (for example, when asked during an interview where the client sees themselves in the future).

Regardless of whether the plan is developed at the beginning or during the skills audit, setting a goal (or goals) to achieve is recommended. They should be:

Goals can be developmental – focused on bridging the gap between what is and what the client wants to achieve (e.g., gaining knowledge on a given topic, mastering a language at a higher level). Goals can also be educational (e.g., choosing a school or training course) or professional (e.g., changing a job).

Next, it is worth breaking down the main, long-term goal into detailed (operational) and smaller actions that lead to their achievement (Individual Action Plans are prepared following a similar principle). The actions can be visualised by arranging them on a timeline.

Maria (22 years old) is studying international relations. With the help of the SAM and working with a counsellor, she plans to find employment in international trade with China. With this goal in mind, she has written a development plan on a timeline (Figure 5).

2023 GOAL: employment in a company conducting trade with China

2022 (February) ACTION: apply for an internship

2022 (January) ACTION: find information on firms trading with China

2021 (October) ACTION: enrol in a course on cultural relations in business

COMPETENCE: discusses the principles of working in an international environment

COMPETENCE: recognises the cultural differences between Poland and China and takes this into consideration in business communications

2021 (February) ACTION: enrol in a course on international law

COMPETENCE: knows the basics of international law

2021 (January) ACTION: enrol in an additional course in Mandarin Chinese

COMPETENCE: knows the Mandarin Chinese language at the B2 level

Breaking down the main goal into intermediate steps is especially important for clients who are “wishful thinkers” about their career. Breaking down the process will help them visualise how many actions need to be taken in order to achieve the goal.

When preparing or revising a plan, you can review the competences diagnosed during the skills audit and verify initial ideas. It is worth considering what is feasible for the client, the foundation that they already have, and what further career direction is indicated by their resources. A review of competences in this case can strengthen the client and show them that they have the basis to implement the scenario they have planned.

When preparing the development plan, consider the time frame in which the goal is to be achieved. A specific date is not necessary – setting a month is sufficient. This time may be subject to change. However, it should be set in advance as something to strive towards – this helps to make the goal realistic. The plan can also include intermediate objectives with actions to be taken. It is useful to place the specific objectives of the plan on a single timeline. This helps to identify and learn how achieving different objectives can affect each other.

The development plan can be prepared with the use of the My Portfolio digital tool, an editable form (in Polish), or one’s own materials (the simplest version is to draw the timeline on a piece of paper and enter the goals and actions together with the planned dates to achieve them).

The skills audit should end with a summary of all the stages and the work performed by the client with the support of the counsellor. The feedback can be oral or written. How detailed it will be depends on the approach of the counsellor or career coach. The timing of the summary and discussion depends on the individual case – it can occur after each stage of the skills audit. It is important to discuss both when and how the summary will be conducted with the client at the beginning of the skills audit process so that they know what to expect.